3. The Frontiers of Monetisation

The two themes of Measurement and Valuation, on one hand, Political Process and Integration, on the other hand, are brought together by exploitation of the concept of the “Monetisation Frontier”, a device to signal thresholds or limits beyond which assessing trade-offs; choices or the consequences of choices on the basis of monetary measures alone are of questionable pertinence. Monetary valuation of environmental benefits or of changes in environmental/social conditions is often seen as providing a common and understandable measure through which different objectives can be traded off. Placing money figures on impacts gives a quantification of the scale of beneficial and adverse effects, and also the investment and the adjustments that might be needed to compensate communities, restore damaged environments and avoid further damages.

However, the necessary conditions for establishing monetary commensurability are very restrictive. Opportunity costs associated with use of an environmental resource are quantifiable only within tightly formalised modelling perspectives that define the relevant set of interdependent production–consumption–conservation possibilities (and hence trade-offs) for the ecological-economic system and for the time frame in question. Relative to these requirements:

- There is scientific uncertainty, and it is difficult to reduce the complexity of biophysical cycles and ecological processes across scales as required for mathematical specification of “inter-temporal production possibility frontiers”.

- With any modelling approach, there will be, in theory, valuation indeterminacies associated with the sensitivity of the equilibrium prices (measuring the opportunity costs) relative to the distribution of property rights and prevailing power structures.

- Due to complexity and uncertainty, there are problems with empirical measurements of biosphere process and social variables, even if the theoretical specifications were resolved. These include the difficulty of achieving robust catalogues of significant short- and long-term environmental damages.

- Societal indeterminacy concerning what is significant and to whom is compounded by these uncertainties, and in turn contributes to them.

These obstacles to applying monetary valuation methods are present at all scales, and for all significant domains of environmental change. They arise from the attempt to transpose traditional economic valuation methodology to new classes of phenomena for which it was not originally devised and where it may not be applicable, namely: extension spatially and materially to the non-produced and largely non-commodified natural environment; extension temporally to the long term of ecological change and sustainability concerns; and extension discursively to an open-ended spectrum of “sustainability” values associated with cultural diversity and ways of life.

Transposition of established concepts to new domains is a legitimate strategy for scientific work. However, there are points where the attempted application contains deliberate irony, as deliberate reflection about contradictions or inadequacies of existing explanatory apparatus contributes to formulation of new concepts.

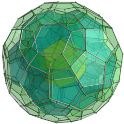

Taking up the challenge of operationalising sustainability (of what, why and for whom?), we introduce a sequence of strong dialectical simplifications. First, we propose that there are two main types of thresholds beyond which assessing trade-offs or the consequences of choices on the basis of monetary measures alone are of questionable pertinence. Either the estimation is scientifically very difficult, or the proposition of a “trade-off” implied by the opportunity cost considerations is deemed morally inappropriate. In Figure 1, this is represented schematically along two axes, those of System Complexity and Value Plurality.

1. we note that sustainability assessments tend to make reference, one way or another, to two sets of principles: “systems integrity” and “ethical integrity”. These are interwoven,

2. but are rooted in different facets of knowledge and motivation. In the prevailing context of commercial justifications for resource mobilisation, the ethical dimension of sustainability can be evoked ironically by applying a sort of “ethical appropriateness” test to each value question. This consists of enquiring about the acceptability of the prospect of conversion of a societal value into monetary currency (viz., in the marketplace), e.g., as epitomised by popular expressions such as “save the whales” or “you don’t sell your own grandmother” that point to things other than purely utilitarian motives for the respect of systems integrity, whether in the environmental or social domain.

Figure 1. The monetisation frontier (adapted from O'Connor and Steurer, 2006)

You are in ePLANETe >

You are in ePLANETe >